1) Never insult writing, neither yours or anyone’s.

“I’ll just have to face the facts, girl, I’m no Tolstoi. Going for a philosophical end there isn’t going to work” Before Watchmen: Minutemen #1 p.3

You

may think this gives your writing humility, or in-universe it gives an

excuse for a character to not demonstrate the exceptional writing skills

he’s famous for, however it just shows poor penmanship. Disrespecting

your own or a character’s literary voice weakens the author’s authority.

The first page of any literary work is the opportunity for the author

to establish authority, to convince the reader to stay and enjoy the

story and this is achieved through two methods; be empathetic and appeal

to the reader’s emotions or appeal to the intellect and hand out

provoking thoughts. By saying: “This is terrible” (Op. cit p. 2) you

just lose everything you gained.

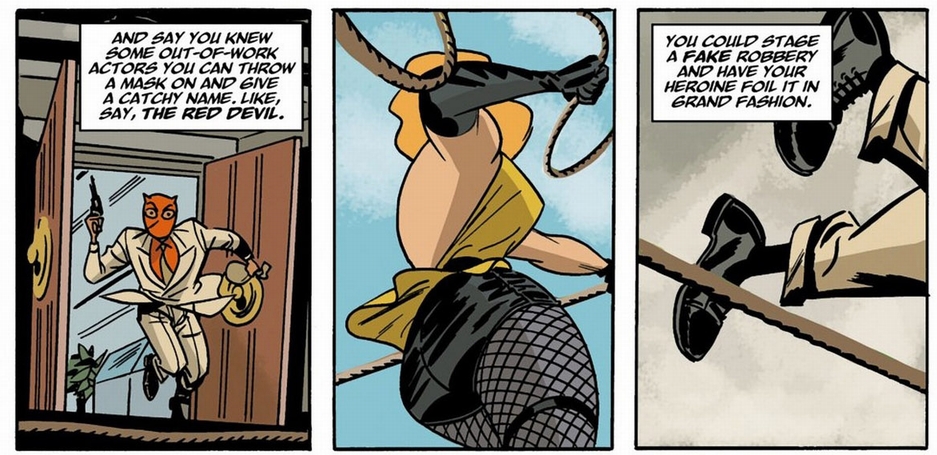

2)You shall not hang lampshades

Writing,

as any other craft, has conventions, these conventions are the

unwritten contract you and the reader sign when the work is purchased or

acquired, “I am going to tell you this story and here are the tools of

the trade I am going to use” In visual arts, such as the comic-book,

monologuing is accepted. Steve Ditko and John Romita Sr.’s Spider-Man

continually monologues as he spins his web around New York City, John

Byrne’s Superman monologues as he fights his way through War Machines in

The Man of Steel

miniseries, we have come to accept it. The original Watchmen always had

an explanation in-universe for monologuing. Rorschach’s Journal, he was

dictating to his own head and later sat down to write it, Doctor

Manhattan’s watching the past and the future happen at the same time,

Alan Moore used these conventions but somehow skipped the thought

balloons relying on expressions drawn by Dave Gibbons, both the words

and visuals perfectly married.

In

the hands of a much inferior writer whose only trick is: “look how

aware I am of how ludicrous comic book conventions are” this becomes

just that, a cheap trick for a quick laugh, that undermines the unspoken

contract between creators and readers, made worse by the fact that

monologuing is used in a straight way throughout the rest of the book.

3) Alternate Character interpretations belong to fanfiction, not in official releases (Brian Herbert’s Syndrome)

Derivative

works have a very tough job, they come after a established property and

while carrying their own goals they must still follow the original. The

biggest perpetrators of this is Marvel and DC Comics, their properties

have gone through dozens of creators while still trying to be

recognizable. Chris Claremont's run on X-men for many has been the

definitive interpretation of the characters, but after Claremont came

much inferior writers who killed off the characters they didn’t like and

resurrected the ones they liked., you cannot read Uncanny X-men as a novel, plots contradict themselves, characterization becomes poor and twists and turns are hard to keep track.

An

inferior writer will always try to establish credibility by correcting

or “improving” a character, he has always wanted or always though

something and when given the writer’s reins, feels free to explore. This

just weakens the character, The Silk Spectre is a respected

superheroine with equal footing to the rest of the Minutemen and

according to Darwyn Cooke she is just a “pretty face” throwing publicity

stunts while her “kike ass” (sic) husband and agent charges for her

appearances.

4)You shall not use “Dark and Gritty”

The Dark Age of Comic Books, brought upon Watchmen and Frank Miller’s Daredevil and The Dark Knight Returns

began because artists wanted to copy that “Dark and Gritty” feel to the

original works without understanding that it was a result of the

deconstruction process. Deconstruction, in the case of Watchmen, meant exploring the consequences of having costumed adventurers running around. Before Watchmen

not only feels like ANY other comic book, playing the superheroics

straight, it gives The Comedian an artificial troubled past as a

justification for his latter fall, while the original novel guides

through that process and lets us gaze into what he has seen, and lets us

in his gradual descent, Here, The Comedian was born broken and just

recites psych-sounding nonsense. You never tell dark and gritty stories,

you just tell stories.

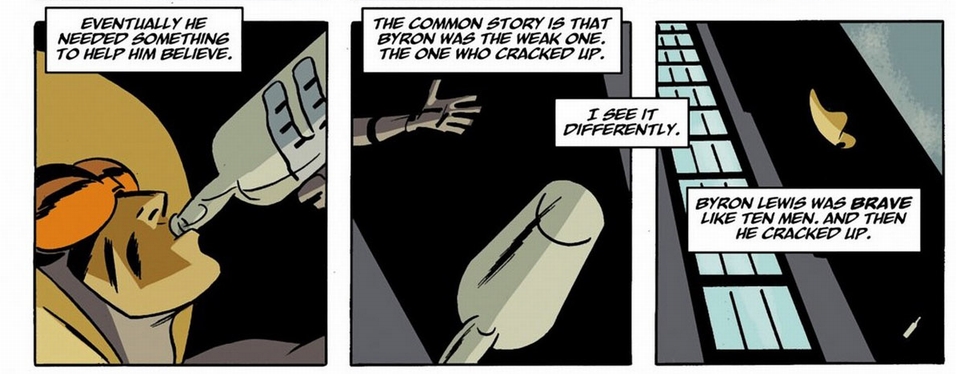

5)

Never give in to the temptation to justify one aspect of the source

material that wasn’t intended to have any further explanation.

The

original narrative of “Under The Hood” provides a laconic ending to the

heyday of the Minutemen, every one of the smiling heroes who seemed

larger-than-life (Except the too human Edward Blake, but that’s the

central theme of the novel) have sad endings. In the case of Mothman he

ends up in a mental asylum and is not given additional details, a moth

unceremoniously burned to a crisp by a candle.

Before Watchmen provides

a backstory and a justification to Mothman’s fall, he starts damaged

and fragile, the process of rise and fall subverted entirely. It removes

the counterpoint and the whole reason to have him as a character, these

are details that, while expanding to the existing mythos, add nothing

and detract from the overall mood of the piece. What you do not show is

as important as to what you show, and sometimes, when showing monsters,

the less you show the biggest and foreboding they are in the mind of the

reader, details just dilute that effect.

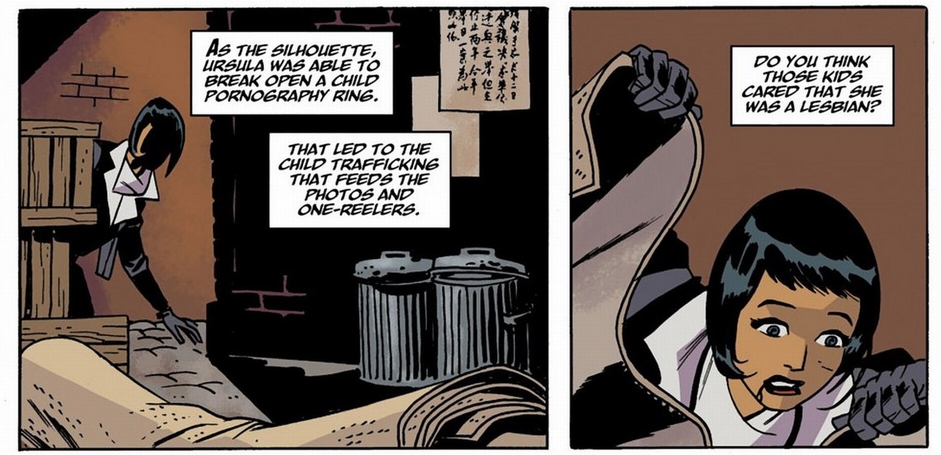

6)Never rely in the power of words themselves, specially for shock value.

Lisbeth Salander in Stieg Larsson’s Millenium series

is a bisexual as a thematic convention to show her detachment to

humanity itself and spiraling alienation, characters in Alison Bechdel’s

stories are lesbians because Bechdel herself is a lesbian and it is an

exploration of her own life, trying to make sense of it, Why is the

Silhouette a lesbian?

It’s part of the overall theme of the Minutemen in general, they really are mystery men.

we know nothing about their personal lives, their public personas are

empty masks, filled by no-ones, it’s because their deaths that we got to

peek a little into their lives. The idea that the comic book reader is

intimate with the masked hero’s real identity is subverted for the first

time in the extracts of Under The Hood, the revolutionary ideas is that not even a fellow hero knew anything about these men and women of mystery.

For

Darwin Cooke The Silhouette is a lesbian because she was in the source

material, and doesn’t show it, gives some kind of pseudoexistential

question, he fails to do a basic writer’s workshop's advice: Show, don’t tell.

And overall, he speaks about a “Child pornography ring” (for the year

of the story a child prostitution ring is more accurate, the child

pornography is a more contemporary fear) that we see nothing about. It’s

more than lazy storytelling, it just becomes name-dropping, a divorce

or the words and images and that is the ultimate sin in sequential art